In April 2021, The New York Times (NYT) retired the term op-ed after 50 years of use. The term initially referred to opinion pieces that sat opposite the editorial page, but since that does not make sense in the digital media world, it was out with the jargon and in with the new name of "guest essays".

At the time, the NYT said these would give audiences a way to grapple with important news by offering important perspectives and world views, rather than fleeting 'hot takes'.

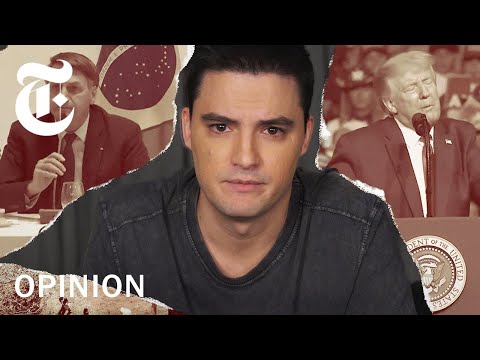

And these are not exclusive to text and print. Four years ago, executive producer Adam Ellick founded New York Times Opinion video, having previously worked at the organisation as a foreign correspondent. It is both a section on the website and a channel on YouTube, where the NYT has nearly hit 4m subscribers.

"Video thrives on personality, humour, attitude, pomp and voice. These are things that younger viewers have come to expect in the medium of video across the internet," Ellick says.

"That was one of the tenets of inventing this department: can we bring New York Times journalism — meaning original reporting — together with visual, opinion storytelling?"

Video gives opinion pieces different options when you factor in how music, tone and scripting can change how a speaker comes across. You will find a balance of comedy and serious reporting on the channel, as well as satire and irony.

Satire in journalism

Take for example Jonathan Pie, a fictional character played by actor Tom Walker, who first went viral six years ago. Pie presents a typical piece-to-camera, followed by satirical 'off-air' comments about the news he has just presented, usually with lots of expletives and insults directed at politicians.

Last month, Walker was hired by the New YorkTimes to do a similar sketch for them. He took aim at the recent 'Partygate scandal' the news that British politicians had flaunted their own lockdown restrictions to hold parties. Pie calls the UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson and the MPs involved "self-serving parasites" and "tapeworms in tiaras".

Ellick says the video is a way to introduce Americans to a story they may have heard about, but have not followed closely.

"It has facts and dates in it, it’s a timeline video if you want to break it down in the most boring sense. It just has a tonne of icing on top to make it watchable," says Ellick.

He adds that it is inspired heavily by the explanatory journalism of Vox. Internally, the NYT calls these types of videos "outrage explainers".

"We’re not calling on Jonathan Pie every day. His personality and tone fit this moment of anger. We thought this story and the news moment were a really effective match with the personality of this character."

Collaborating with content creators

This falls under a broader initiative from the NYT to expand the voices featured on the platform. Not every contributor the publisher hires is, or will be, as outlandish as Pie. But when they are brought onto the platform, they are allowed to do what they do best (with some minor tweaks).

Johnny Harris is a filmmaker, journalist and senior producer who has worked for Vox Media. He also runs a YouTube channel with 2.3m subscribers, well-known for its highly visual, graphic led, deep-dive explainers on technical subjects. Harris's collaboration with NYT is loyal to his own style.

The same is true for people like Felipe Neto, a famous Brazilian YouTuber with 43.8m subscribers. He is known for goofy videos but is also one of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro's loudest critics. Both of those elements can be seen in his collaboration with NYT.

The strategy goes beyond introducing the NYT to the creators' existing audiences and vice versa. These are creators that would be unlikely to write a column, so the video brings new kind of voices to the publication.

"We don't want to sterilise these voices and conform to what they think NYT wants them to do. We want to use them for their voice, we're hiring them and collaborating with them because we love their art, visual style or commentary," continues Ellick.

"I wake up every morning wondering who has something interesting, novel, assumption-challenging to say about the world who we wouldn’t feature in text or print, but has a legitimate or credible voice or an interesting perspective."

Rigour

The Opinion video team make sure that claims are fact-checked, the video is framed ethically and there are no legal or ethical issues. There are also red lines around conflicts of interest and hate speech.

Contributors are vetted. Jonathan Pie has done similar collaborations with Russian state-affiliated media channel RT, for example, which he confirmed in 2016 was licenced content and he has no ties to the organisation.

When looking into Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his covid policies, Ellick hired an Indian journalist to vet dozens of potential contributors. They settled on the comedian Kunal Kamra because of his knowledge of the topic but also because he speaks up in a country that limits free speech.

Journalism meets opinion

Not all of the contributors are content creators; video is also a powerful medium for giving sources a voice.

NYT Opinion ran an investigative video series in 2019 called Equal Play, which exposed Nike for not offering maternity leave to sponsored female athletes.

To do this, they convinced three athletes to break their non-disclosure agreements with Nike. Nike and three other apparel companies changed their policies within weeks after public outcry.

"We can all imagine what the sterile version of this news story looks like," says Ellick.

"My team took that original reporting and put the breaks on. We said: ‘What can we do to transform this reporting and make it pop on the internet?’"

The answer was to make a video starting with a fake Nike advert, using the same visual language and rhetoric, but quickly fading into a serious video journalism story. 18m people viewed the video featuring athlete Mary Cain.

What about Ukraine?

When it comes to major breaking news, such as the war in Ukraine, timing plays an important part.

The team is currently brainstorming ideas and have started to reach out to authors and YouTubers who have spent their lives commenting on the former Soviet Union and who demonstrate "a lot of attitude and personality". But there is no rush to publish.

"This moment is going to be different today than it will be in three weeks," says Ellick.

"If we have a voice that is quite sensitive, then maybe the story isn’t ripe enough for them right now but it might be in a month or two, when either our audience becomes more immune to the story, or the story becomes more absurd."

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Why publishers can no longer ignore social video

- Depth not scale: How Times Radio is building an engaged YouTube following

- Meet the media innovator breaking down barriers between Polish and Ukrainian women

- Brian Whelan from Times Radio on growing a successful YouTube news channel

- Washington Post opinions editor David Shipley on gearing up for the US election