This article was first published by the European Journalism Centre (EJC), an international non-profit organisation based in Maastricht, the Netherlands, and dedicated to promoting high standards in journalism through the training of journalists and media professionals.

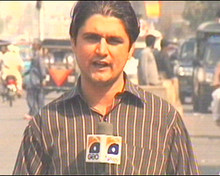

On 13 January Wali Khan Babar became the first journalist to be killed in Pakistan in 2011, but he may just be one of many this year in a country that, with sixteen killings, recorded the highest death toll for journalists and media staff last year, according to the International Federation of Journalists.

These killings have created a sense of fear that affects all media professionals in Pakistan and is felt most poignantly by those working in the conflict zones. The toll "is still unacceptably high and reflective of the pervasive violence journalists confront across the country", said Asim Qadeer Rana, secretary general of the National Islamabad Press Club.

"For many years, journalists in Pakistan have been murdered by militants and abducted by the government. But with the rise in suicide attacks, journalists risk their lives by simply covering the news", he added.

Pervez Shaukat, president of the Pakistan Union of Journalists, has warned that in the current climate of violence members of the media shouldn't depend on the government's help.

"We can't expect the government to protect us since nowadays even our rulers do not feel safe."

It is the responsibility of media organisations to protect their staff, says Shaukat.

Pakistan's journalists and media have been working under increasing pressure these past few years. The threats and dangers related to journalistic work in conflict zones were especially blatant in insurgency hit areas, such as the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP), the tribal belt bordering Afghanistan and parts of Balochistan, where military strives to flush out insurgents. Both sides actively coerce the media into producing news coverage that they deem friendly to their cause and journalists are often violently attacked when they fail to satisfy those demands. Police, civil society organizations, lawyers and others also commonly harass journalists. Tension between the government and some major media organizations had an additional impact on media personnel, particularly with regard to their long-standing struggle for decent wages and working conditions, including protection from physical injury.

From 2007 and for two long years, it was practically impossible for journalists to perform their duties freely in the Swat and Buner districts of NWFP, as groups associated with the Taliban strengthened their position and their armed struggle against state forces intensified. "It was like walking on a knife-edge", according to one journalist who experienced the situation first hand.

"In order for us to insure our safety, we had to respect the wishes of both the militants and the military", he said.

Now, however, journalists believe that the situation has returned to normal, following the defeat of the militants and the Taliban by the security forces.

Military operations in most of the seven tribal agencies (subdivisions of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, or FATA) had established relative calm by the end of 2009. Media personnel were less at risk of injury in their line of duty. While thirteen journalists were killed in the tribal areas from 2006 to 2008, none were reported killed in the period under review. Still, it appears that reports of threats and attacks on journalists have diminished only because there are far fewer media personnel left in the tribal areas.

Elsewhere in NWFP the situation remains unchanged, underscored by a suicide bomb attack undertaken against the Peshawar Press Club on 22 December 2009. The attack killed two club employees – Riaz-ud-Din and Mian Iqbal Shah – as well as a female passer-by, and injured fifteen people, including three club employees.

Balochistan - Information Vacuum

"Stop this biased reporting or get ready for serious repercussions" — this was the threat given to a local journalist working for an international radio in the Balochistan province. The threat came after the journalist reported that Baloch separatist groups had banned the raising of the Pakistan national flag and the singing of the national anthem in government schools in the province. Journalists and media workers in Balochistan – Pakistan's vastest province – commonly face such threats.

While the armed struggle surrounding the separatist movement flared anew in recent years, journalists and other media workers receive no training concerning work in hostile environments. Yet they must contend with pressures coming from all fractions, making self-censorship the universal norm for journalists in Balochistan.

The difficulties are exacerbated by an enduring failure to provide adequate professional training and the prevailing sentiment that journalism is not a profession but merely a way to secure financial or political benefits by other means. In addition to that, media proprietors refuse to pay reasonable wages and take the necessary measures to protect the safety of their staff.

On 9 February 2008 senior journalist, Chishti Mujahid, was murdered in Quetta, the provincial capital. Yet to this day, the police investigation remains in a state of paralysis and no suspect has been identified, let alone apprehended. It is reported that the police halted their inquiries after the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) – one of the separatist militias operating in the province – claimed responsibility for Mujahid's murder several days after the killing.

Mujahid was a doctor by profession but he also worked as a journalist for 38 years, contributing regular articles to the Jang group's weekly Akhbar-e-Jahaan. He was murdered after filing a routine news report about the killing and burial of Baloch separatist Mir Balach Murree in Afghanistan.

There was nothing controversial in the article, but the editors of the paper added a headline reading, "He who claimed a separate state could not find two yards of land for burial in his country". It is believed that this was the primary motive for the murder.

Many other local journalists regularly experience harassment, intimidation and obstruction in their work. In one instance, Kazim Mengal, chief reporter of the Express, and his cameraman, Mahmud, were harassed by security forces and their equipment taken away as they sought to report on the Sandak Gold Project in Chaghi district, despite the fact that both had permission and clearance to access the area.

The few local journalists and photographers affiliated with prominent international media organizations appear to be more prone to threats from separatists who demand media space to air their views and order restrictions on reports that speak of their illegal activities. One journalist, working for an international service, said he had received numerous threats by phone, and is now scared to go home from his office in the evenings.

"Every motorbike passing near me heightens my fear", he said.

Media and government blame each other for poor working conditions

The media, like many other economic sectors in Balochistan, suffers from neglect, even though, as the PFUJ points out, newspapers benefit from a wide range of government tax concessions and low duties on imported newsprint, ostensibly offered to assist them in paying improved wages. But for the Jang Group, the failure to offer decent wages is rooted in the tensions it has with the government, which withholds advertising from the group, under the pretense, that its newspapers and channels provide an unbalanced and unfair coverage.

As a result, the human and social rights of Pakistani journalists are continuously violated. They are denied health insurance, a safe working environment, the right to form trade unions and earn minimum wages, as well as other benefits secured under the Newspaper Employees (Conditions of Services) Act. The Seventh Wage Award for journalists and newspaper staff, announced in 2000, still remains only partially honoured. Furthermore, the industry as a whole suffered massive job losses over the past year, with about 600 media personnel dismissed, according to the PFUJ. In most cases, those sacked did not receive the payments owed to them.

The journalists in Pakistan are believed to be committed and hard working, said Rana.

"I have witnessed many dangerous episodes while working as a journalist in Pakistan, but I have never seen journalists more committed than they are in this era. Pakistan was declared the world's most dangerous country for media work last year, and journalists there are confronted with serious challenges."

There is no denying that journalists in this country are brave enough to face the dangers associated to their job. We should not only appreciate their work, but also provide opportunities for them to polish their skills, help them to face the threats made upon their lives and provide them with decent working conditions.

Time and again, we hear of fellow journalists' bullet-ridden bodies being found by the side of the road. And of course, the perpetrators are never caught. The five orphaned-children of slain tribal journalist Hayat-Ullah Khan are still waiting for answers as to the identity of those responsible for the deaths of their father, mother, and teenage uncle.

They were murdered after Khan published photos that attest to the intrusion of US forces into Pakistani territory.

Kaswar Klasra is a correspondent for the Nation in Islamabad, Pakistan. He has worked as a war correspondent in Pakistan's conflict zone where the Pakistan army is still fighting militancy and terrorism.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- 40 essential newsletters every journalist should read

- The Bristol Cable embarks on solutions journalism project about the future of cities

- EJC launches £3m scheme to fast-track solutions journalism in Europe

- Tip: A freelancer's guide to solutions journalism

- Launching your audience engagement strategy: lessons from Krautreporter's Playbook