Coverage of the trial has raised some interesting ethical questions for the press

Sky News journalist Trygve Sorvaag, live-tweeting the trial of Anders Behring Breivik - the man who admitted to the killing of 77 people in the attacks in Norway last year - reported the following quote from Breivik on Thursday:

"I think it's horrible having to do these actions to get my message out. Blame journalists who stop him spreading his message. #Breivik"

Breivik's stance on journalists raises interesting questions about the role played by the media in his ongoing trial. Breivik has pleaded not guilty to acts of terrorism and mass murder.

As the world's media gathers in Oslo for the trial, now in its fifth day and ongoing, much of the press find themselves in a troubling catch-22 situation. On one hand, huge public interest means that journalists must respond with an appropriate amount of coverage and analysis. However, fears have surfaced that this intense media glare is what Breivik was hoping to achieve. Although the first day of the trial was widely broadcast and reported on, the debate on media restrictions has dominated coverage.

In an article published by Newsweek and Swedish daily Dagens Nyheter before the trial, Norwegian reporter Aasne Seierstad summed up the dilemma.

She wrote: "Are we puppets on a string, or are we doing what's right and necessary?"

As the trial progresses, this feature aims to look at and explain some of the key media issues which have surfaced during the reporting of the trial, and outlines the key reporting laws that all journalists need to be aware of.

Live-tweeting from court

Norwegian media lawyer, Jon Wessel-Aas, who is also secretary general of the International Commission of Jurists, Norwegian section, gave Journalism.co.uk an outline of the legal issues facing journalists live-tweeting the Breivik trial.

"In criminal proceedings in Norway – unless specific restrictions to the contrary are imposed by the court in a formal decision – the press is at the outset free to report, in words and writing, anything that goes on or is said in the court room, this also covers live reporting via social media or other interactive media.

"However, when it comes to photography and audio or video recording and broadcasting, the main rule is the opposite; it is forbidden while the court is in session, unless the court has specifically allowed it."

As the court's live TV feed is subjected to a ban on broadcasting any of Breivik's, or his victims', testimonies, many people across the globe are likely to choose to follow the Twitter feeds of journalists inside the court room for updates.

But free speech blogger Daniel Bennett told Journalism.co.uk he believes substituting reporting Breivik for tweeting his quotes leads to coverage fraught with problems. He also blogged about the issue for Index on Censorship.

"The problem for live-tweeting journalists is that it is hard to do any more than simply relay what Breivik is saying," Bennett said.

"Live-tweeting is a time consuming exercise and it is difficult to consistently provide background information, context and challenge Breivik's unsavoury evidence."

He added that the "natural news instinct" is to repeat Breivik's "most shocking" comments, "potentially causing additional suffering or inspiring extreme right-wing nationalists."

Indeed, Breivik has been a trending topic on Twitter consistently throughout his testimonies, as up to 800 journalists are on hand to relay his rhetoric back across the web, and around the globe.

Notable UK-based tweeters have included Sky News journalist Trygve Sorvaag, whose frank quoting from the courtroom included:

"#Breivik describes all journalists as political activists and want[s] to kill them"

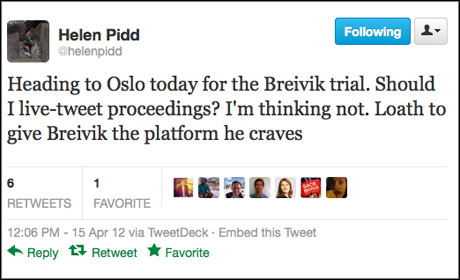

As Bennett flagged up in his Index blog post, Guardian reporter Helen Pidd, tweeted on Tuesday: "Heading to Oslo today for the Breivik trial. Should I live-tweet proceedings? I'm thinking not. Loath to give Breivik the platform he craves".

And she went on to discuss the ethics of live-tweeting the trial with her followers and colleagues.

"@pollycurtis Well, I think with a report you have context. With tweets I'd feel I was publicising his warped soundbites without criticism."

Twitter users who replied to Pidd's comments were divided over whether she was justified in this self-censorship. However, Pidd disclosed that her colleagues at the Guardian had agreed that it was "not morally wrong to live tweet the trial" and went on to tweet the proceedings in its minutiae.

Bennett believes that the only way to overcome the ethical issues surrounding live-tweeting is incorporating the tweets into liveblogs, and longer articles where there is more space for additional analysis.

"But even then", he says, "there is a difficult balance to be struck between accurate reporting and providing a platform for an abhorrent ideology which led to the killing of 77 Norwegians."

Ethics of reporting and TV broadcasting

Broadcasting from court in Norway is usually forbidden, however the decision lies with the discretion of the professional judges of a case before the trial begins.

Jon T. Johnsen, professor of law at the University of Oslo, told CNN: "I think the case is being aired because of the large public interest. We haven't had any comparable case like this since the age of television started."

A court order has already banned all televised outlets from showing testimony by Breivik or by his victims. On 13 April, the Norwegian Supreme Court rejected an appeal by the press to revoke this restriction. Judge Wenche Elizabeth Arntzen rejected Breivik's claim that airing his statement was a human right.

Lawyer Jon Wessel-Aas explains the court's reasoning behind these restrictions to Journalism.co.uk:

"The court's main arguments for restricting the TV broadcast with regard to Breivik's testimony and examination, was twofold: 1) the court held that since one of Breivik's main motives with the actions he is on trial for, was to spread 'the word' of his ideology, the court shouldn't contribute any further than necessary to fulfilling this ambition, by allowing his testimony to be broadcast – also because this could inspire him to make more of a show of it, and 2) that it would add to many of the victims' grief if this was broadcast, and that it could even be harmful to young victims who chose not to be in court, if they were exposed to broadcasting from his testimony at home on TV or on the internet."

But, similar to the media reaction, Wessel-Aas has criticised the court's decision. Oslo District Court allowed broadcaster NRK to air most of the first day of the trial live and pool the footage, although NRK chose to remove the sound from the most detailed descriptions of the killings.

However, Twitter was awash with outrage on Monday with messages expressing disgust at beholding Breivik's every move, as media TV cameras remained fixed on him for almost the entire proceedings, often in silence.

Speaking against the restrictions, Wessel-Aas told Journalism.co.uk: "His testimony is the part in which the public can gain insight into who this man is and what has motivated him, also in a larger political and sociological context in Norway and Europe."

Wessel-Aas refutes the accusation that broadcasting Breivik's testimony would give an undue platform to the accused, and goes so far to say that denying TV coverage, while permitting print coverage, could lead to a potentially more dangerous situation.

"As those of us who have followed the trial so far will have experienced, Breivik hasn't really been allowed to use his testimony as a stage. He is in a court of law, where the court itself has the power to keep things in a frame which is relevant to the case.

"Also, with the rest of the media being allowed to report freely from the proceedings, every word he says is basically reported live, anyway. The only difference is that instead of hearing and seeing him, the public at large is left with the interpretations and angles of all the commentators in the media, trying to convey how they perceived all the nuances that are lost, when only the words are reported."

Trygve Monsen, a former Afternposten journalist who is tweeting the case live from court for the German press, told Journalism.co.uk from court on Thursday that the ban went "against the principles of openness of the judicial system".

But the decision to restrict media coverage has raised fundamental questions regarding the impact of mass exposure of the trial on Norwegians affected by the events of 22 July 2011.

Kristine Lowe, founder of the Norwegian Online News Association (NONA) was working at newspaper Verdens Gang when Breivik's bomb went off in the neighbouring government headquarters. As a journalist who experienced the violence first-hand, Lowe said that day's events were nothing short of "soul-destroying", but has found the extensive media coverage to be "exceptional".

She wrote of the trial on Facebook: "It was truly awful to watch, especially when the state prosecutor read the list of all the victims - so many victims, and so young - even in the government HQ where the bomb went off, next door to VG where I was working - there were so many young victims. At the same time I needed to watch it."

She added that "having been so close to where the bomb exploded" and read his manifesto,"it feels like something I just have to keep an eye on".

But she added that having spoken to someone else who had been in the Oslo court she "felt grateful that I didn't have to cover the first day of the trial".

Sky News reported this week that "too much news about Anders Behring Breivik is frustrating the people of Norway."

"Most citizens", the report continued, "do not believe the continuing coverage...will add important details about the attack that claimed 77 lives last July."

In fact Norway's second largest tabloid newspaper Dagbladet, is offering its readers a 'Breivik-free' edition of their website. By pressing a button on the top of the homepage, readers can remove all mention of the high-profile trial.

However Torry Pedersen, editor-in-chief of Verdens Gang, the tabloid where Lowe was working on the day of the Norway attack, decided not to feature a similar tool on the VG page. "The media has worked hard for openness on the matter", he told Journalisten.no.

Jon Wessel-Aas also gave his response to the Dagbladet 'Breivik-free' button: "I am sure there are members of the public who appreciate such an option, but only the statistics will prove whether this was actually something which met a public demand.

"My general impression is that many members of the general public are following the trial and the coverage of the trial quite closely."

Media law in Norway: Key points for journalists

The BBC's Jon Sopel has observed that Breivik would not have as much room to express himself in a British court. Breivik was allowed to read a 30-minute prepared statement in court on Tuesday, which was widely quoted on Twitter and in the global press.

It should also be remembered when reporting the trial that it features no jury at this stage, but is instead made up of two professional judges and three lay judges (members of the public chosen for the case who have the same powers as the professional judges). In this court, the five judges will hear Breivik's case, decide whether he is guilty or not, and then if he is found guilty, they will also sentence him. These judges are not subject to the same statutory anonymity that jurors in Britain are.

Tim Crook, head of media law and ethics at Goldsmiths, University of London, gave Journalism.co.uk an outline of the fundamentals of Norwegian media law.

"It is very rare for the world's media to be covering criminogenic-legal stories within Norway. Traditionally, Norway has been much more flexible in recognising the privacy and emotional needs of crime victims, defendants and witnesses and has traditionally made many more compromises in terms of open justice compared to the UK position.

"The decision making has always been jurisprudentially and socially rational.

"The country prides itself on interrogating the balancing of human rights with state and corporate power and authority", he continued.

Reporting minors involved in court cases should always be treated with sensitivity, particularly given a crime in which such a high number of victims and survivors are children.

Wessel-Aas gave Journalism.co.uk this advice when considering reporting the youngest victims:

"The media should be diligent in its approach in this area – and on this point ethics and law will partly overlap. I think, as a rule of thumb, consent should be the basis for any reporting which includes images of or other identifiable details of the teenage victims."

Journalists interested in the ethics of reporting the Anders Breivik trial from the perspective of the child survivors of the events of July 22 2011, can read a report from the Norwegian Ombudsman for Children, composed with input from nine survivors.

The group understands that media interest and coverage of the court case will be extensive, and has called for the media to be considerate during interviews and in the overall coverage of the trial.

Free daily newsletter

If you like our news and feature articles, you can sign up to receive our free daily (Mon-Fri) email newsletter (mobile friendly).

Related articles

- Ethics, diversity, influence and digital transformation: 10 trends to watch in UK journalism

- New guidelines call for the abolition of kill fees and fair payment practices for freelance journalists

- Seasoned reporting: charting changing tastes in food journalism

- How to report on homicide and interview grieving families

- Reporting on homicide and interviewing grieving families, with Tamara Cherry